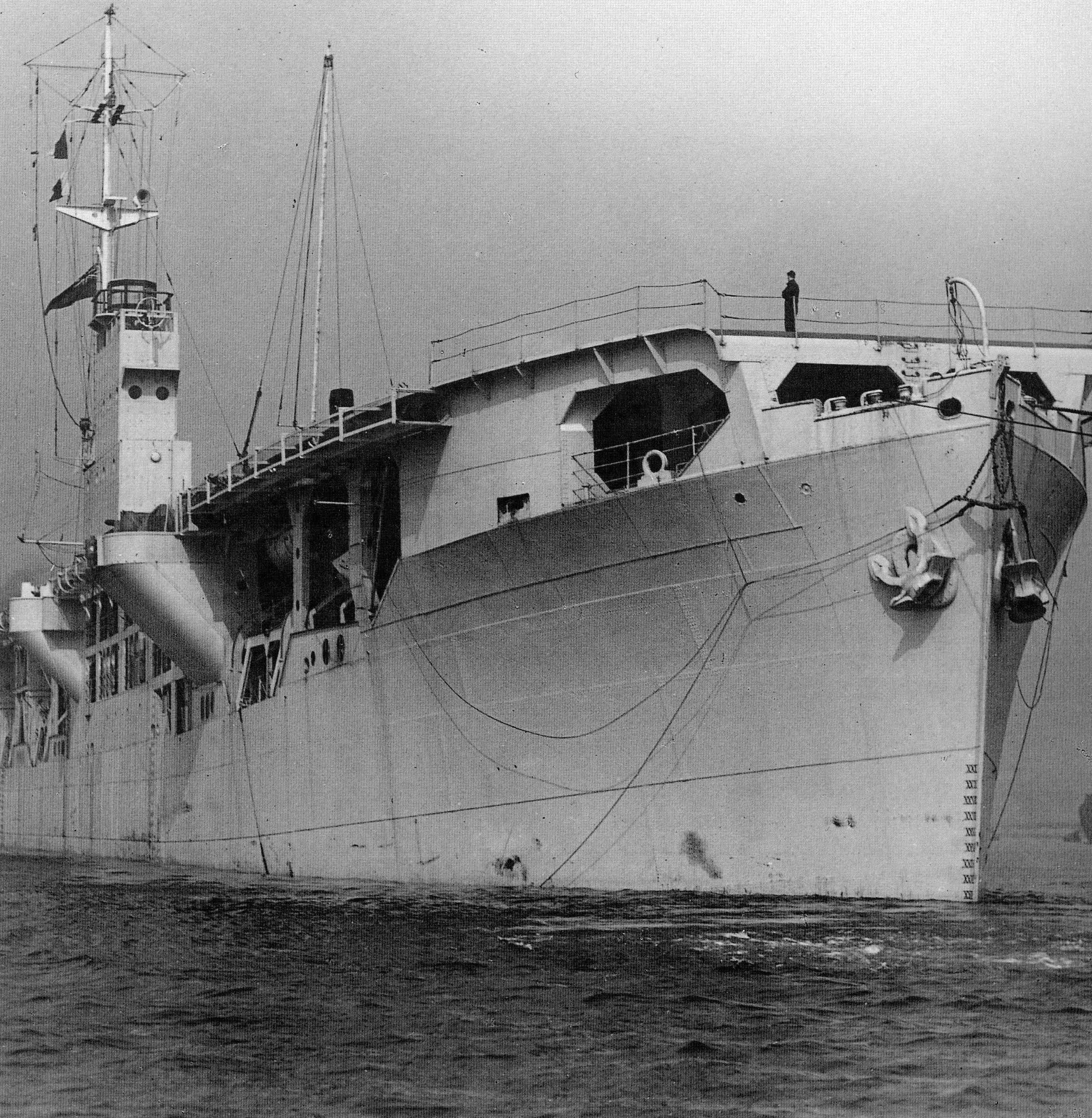

New lift - Jan Hudig (1970-73)

INTERTANKO started its life in Norway in the building of Norges Rederiforbund, the Norwegian Shipowners’ Association, a solid edifice next to Oslo Town Hall.

Tormod Rafgård, a lawyer working for Rederiforbund, joined INTERTANKO as its Secretary General and was assisted by his secretary Mrs MT Parker.

Rederiforbund extended to INTERTANKO the use of its printing and back-up office facilities. The residual funds from London of the International Tanker Owners’ Association - £11,740.49 - were transferred to INTERTANKO and membership fees were set at $50 per ship up to 50,000 Gross Register Tons and $100 per ship over 50,000 GRT. An income of $58,000 was generated.

Invitations had been sent to independent tanker owners in 10 countries to participate in the foundation of INTERTANKO, to "provide a forum for exchange of views and to take active steps toward the protection of the interests of independent tanker owners" as the 1971 Annual Report recorded it.

Jan Hudig of the Netherlands shipowner Phs Van Ommeren was elected the first Chairman, backed by Jørgen Jahre and Filippo Cameli of Italy as Vice-Chairmen. Erling Næss, John Kulukundis from Greece and Mærsk McKinney Møller from Denmark completed the Executive Committee.

The growth of INTERTANKO’s membership in its first year of existence was phenomenal. By January 1 1971, 25 million dead-weight tons of tanker ships were entered into membership. Within a month the tonnage had reached 31 million, comprising 500 tankers. By September the number of ships had doubled to 1000, and the tonnage jumped to 70 million deadweight tons.

Council of national representatives

INTERTANKO set about creating a Council of national representatives elected in proportion to entered tonnage, and in January 1971 the first Council meeting was held. By September, the second Council, a body of 26 members - each from a different company - from 12 countries assembled. The original 10 member countries - Denmark, Finland, France, West Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom - had been augmented by Australia, Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, Israel, Japan, Liberia, Spain and the US.

The growth continued into 1971. Representatives from 80 companies attended the 1971 Annual General Meeting in Rome and over 1972 membership grew to 100 million deadweight tons - estimated at 70% of eligible independent tonnage.

By the end of 1972 no less than 87 Norwegian companies were Members - a number which by consolidation and change over years actually fell to 39 by 1994. Only 23 of that early 87 survived to 1994.

Early on, INTERTANKO was faced with challenges. In 1967 the tanker Torrey Canyon had stranded itself on rocks off the Scilly Isles to the south-west of Great Britain - an area of exceptional beauty - and spilled its cargo of crude oil. The disputes about liability for compensation and the funds available led the Intergovernmental Maritime Consultative Organisation (IMCO) - the forerunner of the International Maritime Organisation - to consider options to make liability and compensation more certain.

Early on, INTERTANKO was faced with challenges. In 1967 the tanker Torrey Canyon had stranded itself on rocks off the Scilly Isles to the south-west of Great Britain - an area of exceptional beauty - and spilled its cargo of crude oil. The disputes about liability for compensation and the funds available led the Intergovernmental Maritime Consultative Organisation (IMCO) - the forerunner of the International Maritime Organisation - to consider options to make liability and compensation more certain.

The result of these deliberations was the International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage - known in short as the Civil Liability Convention or, shorter still, as CLC of 1969. CLC imposed strict no fault liability on tanker owners to compensate victims of oil pollution from tanker casualties, but allowed those owners to limit their liability at fixed, high, monetary levels.

Intergovernmental Conventions take a long time to come into effect and, recognising this, tanker owners had created the Tanker Owners Voluntary Agreement concerning Liability for Oil Pollution (TOVALOP) in 1969. TOVALOP is a voluntary agreement by the industry to accept responsibility up to certain levels that a tanker owner would clean up oil pollution resulting from a casualty of his ship and would compensate victims of the oil pollution.

Tanker owners entering TOVALOP join the International Tanker Owners’ Pollution Federation (ITOPF), which administers the TOVALOP agreement. In practice, this means that ITOPF is the body whose marine and biological experts supervise or advise on work on site to clean up and restore damaged seas and coasts.

Following settlement of the tanker owners’ contribution to oil pollution response, the focus turned to the responsibility of the cargo owners - the owner of the oil that pollutes. Negotiations led up to the adoption in 1971 at IMCO of the International Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage - the Fund Convention - and the creation of the International Oil Pollution Compensation (IOPC ) Fund. A voluntary agreement, cumbrously known as the Contract Regarding a Supplement to Tanker Liability for Oil Pollution (CRISTAL), was set up by the oil industry, topping up compensation provided by TOVALOP to make voluntary provision until the Fund Convention received widespread acceptance.

The tanker owners thus accepted responsibility for the first line of spill liability and the oil interests agreed to take responsibility and fund compensation as a second line of defence for bigger or more damaging oil spills. The voluntary agreements TOVALOP and CRISTAL were intended to be temporary expedients but 25 years later the main Conventions, CLC and Fund, have still not achieved universal acceptance and, although their end has been signalled, the voluntary agreements TOVALOP and CRISTAL are still the source of compensation to oil pollution victims in many countries.

One of the first issues to occupy the attention of INTERTANKO was, therefore, oil pollution liability. At this time, INTERTANKO was not represented at IMCO. However, Tormod Rafgård had been part of the Norwegian government delegation drafting CLC so was familiar with the workings.

Rafgård represented INTERTANKO through the International Chamber of Shipping, ICS, at the Fund Convention discussions. INTERTANKO sent members to the Tanker Committee of ICS and relied on ICS to represent tanker interests through ICS’ Consultative status at IMCO.

Not every government was happy with CLC and the Fund. In the US, certain states such as Florida which maintained jurisdiction over their coastlines, imposed different liability provisions on shipping.

INTERTANKO’s Council deplored this and "emphasised the significance of the impossible situation connected with uninsurable unlimited liability that has been imposed on shipowners in certain states in the US". This was nearly 20 years before the US passed the Oil Pollution Act in 1990.

This was not the only issue on which the US attracted INTERTANKO’s concern. Congress was looking at a flag preference bill to encourage American registered shipping or, as INTERTANKO put it, "a general discrimination of non-US flag tankers". This time the move was voted down in Congress.

Currency squeeze

There were other concerns. Sterling, and then the Dollar, had slid dramatically in value in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Sterling had been devalued in 1967 and abandoned where it had persisted as an international reference currency in the oil trade, including shipping freight rates, thereafter. In 1971 the Dollar was devalued, and the post-war Bretton Woods agreement of fixed international exchange rates was abandoned. Currencies were allowed to float and the Dollar floated downwards.

This hit tanker owners hard. Very many ships were tied up on long-term charters to oil companies, with Dollar-related (or Sterling-related) freight rates providing the income. The expenditure, however, could be in a variety of different currencies for crew, maintenance, insurance and debt servicing on loans for purchase of the ship. The effective income slid. A combination of falling Dollar (and Pound) and rising Yen - the currency of the leading shipbuilding nation - squeezed an estimated $750m out of shipping between 1967 and 1971. At the same time, inflation also accelerated so owners were squeezed from several angles.

In 1971, oil companies were approached by tanker owners suffering from the squeeze to agree a means to compensate for this slide. The oil companies had previously responded positively to approaches from oil producer countries for an improvement in Dollar-related prices paid by the oils. An increase of 8.49% in posted prices - the price paid to the government for the oil - had been agreed. Tanker owners received a much less sympathetic ear and no general agreement for an increase in charter rates was forthcoming, although a few owners did receive some ex-gratia compensation from certain oil companies.

Other approaches were required to solve the currency problem. INTERTANKO reflected that "as there seem to be no reasons to believe that any permanent stabilisation of currencies will be achievable in the foreseeable future, owners are likely to be faced with serious problems in the years to come". Shipowners, like the population at large, had to get used to the effects of inflation for the next 20 years.

One way to redress the balance, at least for voyage charters, was to adjust the freight index system. This system, now known as the Worldwide Tanker Nominal Freight Scale, or Worldscale for short, is a method of providing an equal net return per day to shipowners for any round voyage between any combination of ports. To remain constant it has to keep up to date with bunker - ship fuel - prices and with the costs for making port calls. As inflation continued, bunker prices and port dues rose. The Worldscale index, which was published annually at this time, often fell behind the rising costs, and tanker owners’ earnings suffered.

The lead time prior to publication of the new index effective on 1 January meant that changes in bunker costs and port dues late in the previous year were not reflected, and the index could be unrepresentative for the whole year.

INTERTANKO was suspicious that oil companies kept bunker price rises back until after the Worldscale Association, which calculated the scale, had collected its data. Worldscale is only an index and owners (and charterers) have to make their own calculations of voyage costs and relate them to the Worldscale index rate: but there are psychological effects in the Worldscale numbers which these calculations produce.

In 1972, a sudden - and retroactive - imposition of sharply increased dues for calls at Middle East Gulf ports caused more concern. Tanker owners who were required to pay these retroactively applied charges were not always able to recover them from charterers despite INTERTANKO’s efforts. Some of the dues increased in April 1972 affected port calls as far back as August 1971.

Meanwhile, the underlying freight conditions over into 1972 were gloomy. INTERTANKO’s market report reflected that "1972 opened with a decrease in freight rates and in the Spring freight rates from the Gulf to Europe were even lower than in 1932". This was despite the continued closure of the Suez Canal.

In June 1972, a Japanese seamen’s strike rendered some 12 or 13 million deadweight tons of oil carrying capacity idle but INTERTANKO said that "freight rates still bore the mark of the surplus tonnage".

In May 1972, 5.7 million deadweight tons comprising 177 tankers were in lay-up. However the market began a recovery. The Japanese strike ended in July and from mid-1972 tanker shipping entered one of its all too rare boom times, which continued into 1973.

Tanker owners were also getting squeezed by insurance rates. The relatively new phenomenon the Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC) of over 200,000 tons of cargo capacity, was incurring an insurance premium that owners of VLCCs found unacceptable. INTERTANKO supported the Mammoth Tanker Owners Co-operation Group in efforts to get the premiums reduced.

A mutual insurance scheme for VLCCs was pioneered principally by Erling Næss - the United Marine Insurance Company of Bermuda - with 18 member companies. The result was that hull insurance renewals for VLCCs in 1973 showed reductions of 20-30%.

INTERTANKO noted: "It has been indicated that the reason for easing premiums was rather influenced by increasing competition than because of improving loss records." A victory for free competition.

Documentary Committee

INTERTANKO turned its attentions to documentary issues. The major oil companies had their own chartering forms but other oil charterers either used these forms or had a variety of old and somewhat obsolescent standard charter forms to choose from, like Warshipoilvoy or the London Form. INTERTANKO created a Documentary Committee and attempted to rectify this deficiency by drafting and issuing Intertankvoy and afterwards Interconsec as up-to-date charter forms.

While the INTERTANKO forms received some endorsement from shipowning and broking bodies, they did not appeal to charterers who perceived their parenthood as indicative of a pro-owner bias.

The exercise was not in vain, however, because INTERTANKO’s Documentary Committee has increasingly produced valuable comments on oil company standard charterparty forms and additional clauses, which have helped to make today’s charterparties better balanced between owners’ and charterers’ interests.

During the early 1970s, pollution control and tanker safety were under increasingly active discussion at IMCO and INTERTANKO made its views felt. IMCO was considering immediate adoption of segregated ballast tanks on tankers to reduce the risk of oil discharge at sea. The cost of conversions would have been enormous and INTERTANKO, and later other delegations at IMCO, promoted use of "load on top" procedures to allow the oil to remain inside the cargo system and not be discharged at sea.

INTERTANKO recognised that the growing attention to reducing oil discharge at sea required opportunities to discharge oily wastes somewhere else, and noted in 1972 that "IMCO has recognised the need to provide oil reception facilities to be utilised by tankers". More would be heard of this issue over the years.

A series of explosions in large tankers and combination carriers (ships adapted to transport oil cargoes or dry bulk cargoes) during water washing of cargo tanks, caused by static electricity sparks and assisted by explosive atmospheres in tanks, led to the promotion of use of inert gas systems to neutralise the flammable atmospheres - purge the oxygen - from tanks.

Inert Gas Systems (IGS) were urged for fitting to combination carriers over 50,000 deadweight and oil tankers over 100,000 deadweight.

INTERTANKO returned to visit London for its 1973 Annual Meeting at which Jan Hudig stood down. Under his chairmanship, INTERTANKO had established itself as a forceful body truly representing the independent tanker owner.

Jan Hudig was succeeded as Chairman by Jørgen Jahre.